Faced with a large minority of Americans who are either stubbornly reticent or furiously opposed to getting the coronavirus vaccine, US President Joe Biden has called on the private sector to require employees of companies with more than 100 people to get the jab.

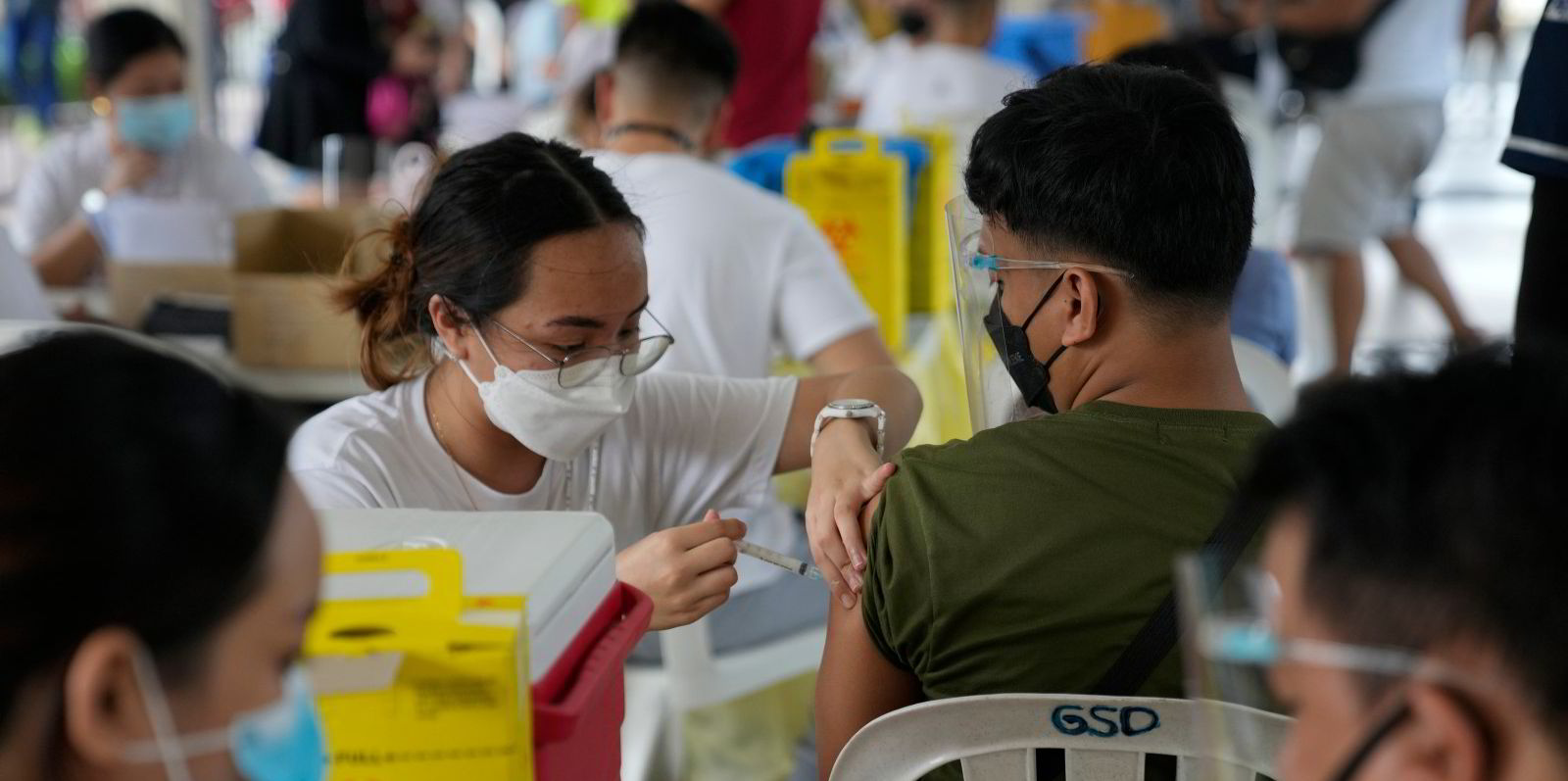

But as the president announced the move from the White House, an effort at the country's ports led by volunteers has been underway for months to provide the vaccine to a population of people who struggle to gain access to being inoculated even if they want it.

In the US, 54% of the country is fully-vaccinated, according to the New York Times vaccine tracker.

And while that number remains stubbornly lower than the White House would like, recent data from the Neptune Declaration Crew Change Indicator showed that 21.9% of seafarers are vaccinated, a 6.6 percentage point improvement from August.

That is better than the vaccination rate in most countries. Yet the small print of the monthly report shows that figure is likely to overestimate the percentage of crew members that have been vaccinated, and the figure still highlights that crew members remain at the losing end of a gross imbalance in Covid-19 vaccine delivery.

Progress in vaccination has largely been tied to efforts in the US and Europe to vaccinate seafarers at ports.

Legions of unvaccinated

And yet, the vast majority of seafarers remain unvaccinated.

Why is it so hard to vaccinate crew members? It's not likely to be a reticence toward vaccination that is plaguing the US, though there have been some reports of reluctance by mariners.

There are shipping companies that are effectively mandating vaccinations for crew members coming aboard vessels, and that is nothing new for seafarers; they have been used to the need for yellow fever vaccines, according to the International Transport Workers' Federation.

For those offered access while at port, the dose of a particular vaccine is not a simple decision, according to seafarer advocates. For example, when only the first dose of a two-dose vaccine is available, a crew member faces a difficult choice of whether to hold out for a one-dose jab or get a second dose at another port.

Ship managers have complained that ensuring access to a second dose is challenging, and it may come with a significant gap between jabs. In the two-dose scenario, it might not even be the same vaccine on offer on the second — Sinovac is available in China, for example, and AstraZeneca or Pfizer in the UK.

Double whammy

But the main problem facing seafarers is a double whammy of the vaccine imbalance.

North American Maritime Ministry Association managing director Jason Zuidema, whose organisation has been involved in developing seafarer access to vaccines at US ports, said the key problem facing seafarers is that on the one hand, they tend to hail from countries where access to vaccines is limited.

On the other hand, seafarers are visiting countries where vaccine access is focused on those nations' own citizens.

Even in ports where vaccines are on offer, it takes a significant logistics dance to provide seafarers with vaccines. Ships often spend short periods at port. Even where crew members are allowed off vessels — which remains a challenge — they may not have the right paperwork to do so, for example, in the US.

Seafarers are not alone in facing difficult access to vaccines. Rich countries raced to provide priority access to their citizens, while poorer nations have been left in the lurch.

And the tragic irony is that while crew members tend to come from countries where access is limited, the countries relying on seafarers are among the well vaccinated. Of the world's top 10 importing and exporting nations, all but South Korea and India have fully vaccinated more than 50% of their populations.

Yet, Biden and other leaders are pushing for booster shots to distribute third doses to their citizens, even as the World Health Organization has called for a moratorium on such booster shots while so much of the rest of the world waits for access to a first dose.

These governments, and those of nations serving as key shipping hubs, need to break out of their policies of vaccine nationalism and deliver doses to the workers that are essential to world trade.(Copyright)