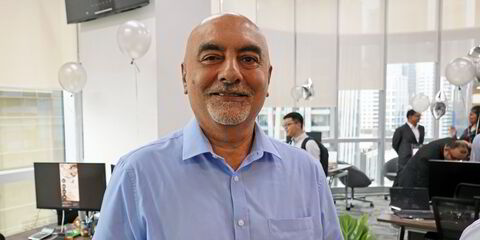

There is no end to the chaotic boardroom battle that started almost a year ago to control giant tanker company Euronav. On a conference call with investors last Monday, chief executive Hugo De Stoop launched a blistering attack on one set of his own shareholders.

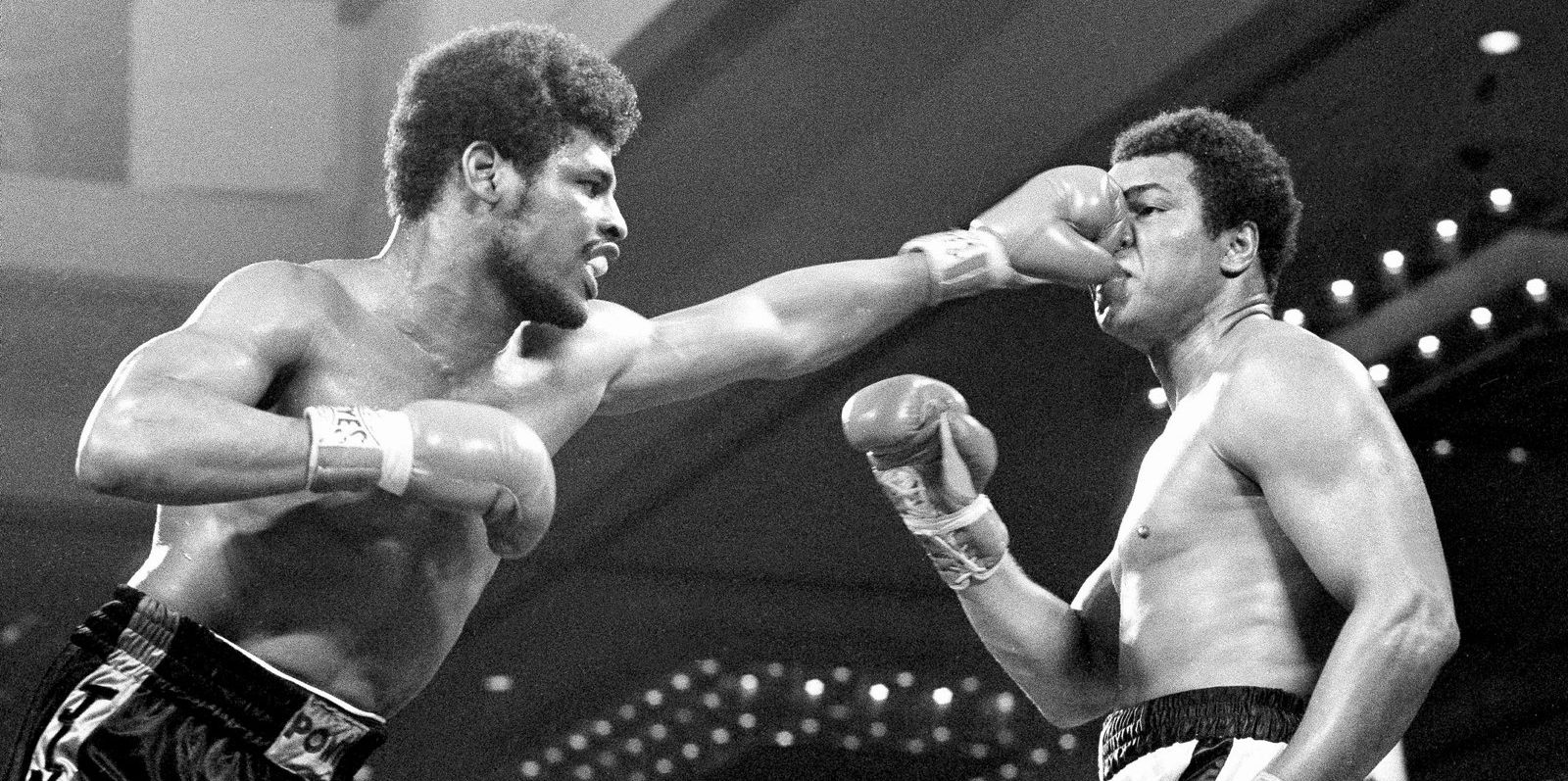

He said they were engaged in a “brutal” and “cynical” attempt to wrestle control of the business without paying for a formal takeover or merger.

The tension around Euronav has increased as the tanker sector becomes increasingly valuable after a major market turnaround.

Expect the atmosphere to become even more fraught in the run-up to a critical 23 March meeting of the Euronav board.

Then Belgium’s Saverys family — the focus of De Stoop’s ire — will try to remove Euronav’s five current supervisory board members and replace them with their own choices.

Standing against will be Norway’s Fredriksen family, which has the general support of De Stoop, and which is trying to put two of its own people on the Euronav board — most notably patriarch John Fredriksen himself.

This bruising fistfight for control of the largest independent tanker owner listed on the New York Stock Exchange has been going on since 7 April last year.

That was when Fredriksen unveiled plans for a merger of his Frontline tanker operation and Euronav — a move that was given an initial price tag of $4.2bn.

De Stoop and other Euronav executives favoured a deal. That move has been strongly opposed by the Saverys family and their company Compagnie Maritime Belge (CMB).

Both warring shareholder groups now own a quarter of Euronav.

Fredriksen exits

On 9 January, Fredriksen suddenly pulled out of the proposed merger in frustration at the impasse with the Saverys family.

This has led to De Stoop and the Euronav board launching an emergency arbitration claim against Frontline for taking “unilateral” action to terminate the deal. On 8 February, Frontline said the case was dismissed and costs awarded in its favour.

This leaves De Stoop in the middle of the ongoing conflict between Fredriksen and the Saverys family or Frontline and CMB.

The Euronav boss said he now wants the two sides to get around the table and hammer out a peace settlement.

But he was furious enough to unleash his verbal fusillade against the Saverys clan for suggesting their desire to bring five members onto the Euronav board would restore “serenity” to the Belgian-based company.

“I found that profoundly unfair,” he told investors on the teleconference call. “There was no tumultuous time before CMB decided to oppose the merger [with Frontline] ... That chaos was brought to us by CMB.”

But now De Stoop believes peace could be achieved if Frontline and CMB agree to put forward two executives each to the Euronav board.

The wider problem with this — even if the Saverys family were to agree, which seems unlikely — is that both sets of investors have competing strategies for the way forward.

The Saverys family wants to split Euronav into two, using cash from a legacy tanker business to build up a separate post-fossil fuels operation inside CMB.Tech.

The latter is already up and running as a company that designs and operates marine and industrial plants run on fuels of the future, such as ammonia and hydrogen.

Fredriksen is unimpressed. He had wanted to operate Euronav and Frontline together as a traditional — but even larger — tanker group of the present as well as the future.

Surging oil demand

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent Western sanctions have disrupted global oil supply patterns and increased tonne-miles for tankers.

They have also put energy security back as the number one priority — over and above decarbonisation and the climate crisis, at least for the moment.

The crude and tanker sectors are booming amid high commodity prices, freight rates and asset values. The big oil majors, such as BP, are pivoting back from renewables towards oil production, while shipowners are keen to get in on the spoils.

Shipowner group Bimco said this week that it expected the strongest growth in 15 years as China emerges from lockdown and oil demand surges.

Euronav’s shares are at their highest level since 2008 despite the ongoing boardroom squabbling. Investors seem calm with the chaos.(Copyright)