Legacy industries are rarely at the forefront of new technological breakthroughs for the obvious reason that they have sunken assets in old technology to protect.

The idea that the oil companies are going to be at the forefront of providing the decarbonised fuels of the future might be long on hope rather than experience.

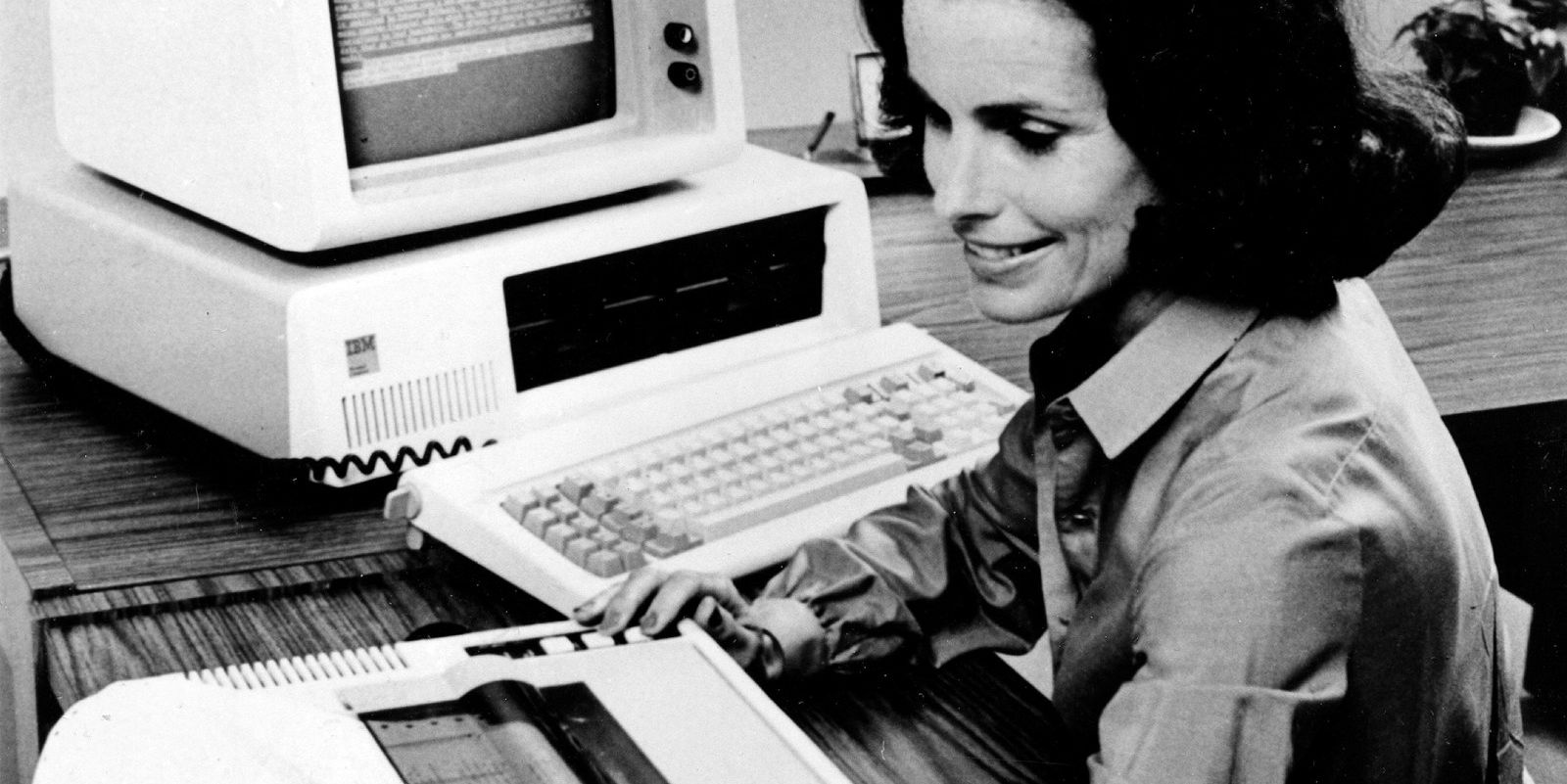

It was new personal computer companies, such as Apple, that pushed the previous giants of the market like IBM into a cul-de-sac.

Legacy brands

And more recently, it was Elon Musk’s Tesla models that really put the vroom into electric vehicles and turned them mainstream.

Now of course all the legacy brands such as Volkswagen and Ford are busily bringing out new electric vehicles to keep up with Tesla, which itself cannot produce enough to keep up with demand.

Liner shipping giant AP Moller-Maersk seems to have already worked out this paradigm. That is why it suggested this week — just as the COP27 climate talks started in Sharm el-Sheikh — that it was putting together a fuel deal with the Spanish government.

The Danish group seems to have concluded that if it wants decarbonised bunkers for its massive fleet, it may well have to provide them itself.

This is why Maersk chief executive Soren Skou met Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez to sign a protocol for collaboration this week to explore green energy production opportunities in the European country.

Morten Bo Christiansen, head of decarbonisation at Maersk, was somewhat more pointed in his comments.

“Today, we buy our fuel from the oil companies,” he said. “But they have not offered us any green methanol at a price we can accept.

“You would have thought that your current supplier would help you find the new juice. But that has not been the case so far.”

The likes of Shell, BP and other oil majors will argue that they are indeed working hard on how to make methanol and other new fuels work commercially, starting with production generated by natural gas.

The oil companies do talk quite a lot about methanol and even more so hydrogen, but it stands to reason that their real interest lies in finding a cleaner home for their fossil fuels.

The conversation of oil executives tends to be peppered with references to the expense of making these new fuels from renewables compared to making them with gas. They want natural gas to be the “transition” fuel. You can understand why.

Certainly, oil companies cannot say they do not have the cash for research and development, given record quarterly profits out of soaring commodity prices.

Fuel logjam

But there is a need to break through this fuel logjam if we are to meet the Paris climate agreement rules, which were aimed at trying to stop global temperatures from rising 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Most scientists in Egypt this week are now saying this is near impossible, but the implications of just sailing through to 2C or more are profound.

Sir David King, former chief scientist to the UK government, said this week that “there is no carbon budget left” and that for a safe world we must now take CO2 out of the atmosphere and make sweeping policy changes in the next five years or face complete dislocation of world trade by 2050.

Yet carbon capture and storage technology is expensive and is currently at nothing like the scale it would need to be. King is talking about geoengineering: giant aerosols in space and some such, but who is going to regulate that in a safe and controlled way?

Meanwhile, Maersk, which has 19 methanol ships on order that enter the container fleet between 2023 and 2025, is taking things into its own hands. The Copenhagen-based company estimates that it needs 6m tonnes per annum of green methanol to reach its decarbonisation targets by 2030.

Skou said the Spain deal has the potential to provide a third of this from a variety of production opportunities in Galicia and Andalusia. Spain’s large coastline and strategic position is also a major opportunity for refuelling merchant vessels.

Fortunately, its own windfall profits in recent years have left it in a position where it can make big investments. Not many shipping companies are quite so comfortably placed — or have management that has been so determined around the climate crisis.

But oil companies need to up their game or risk being left behind like IBM.(Copyright)