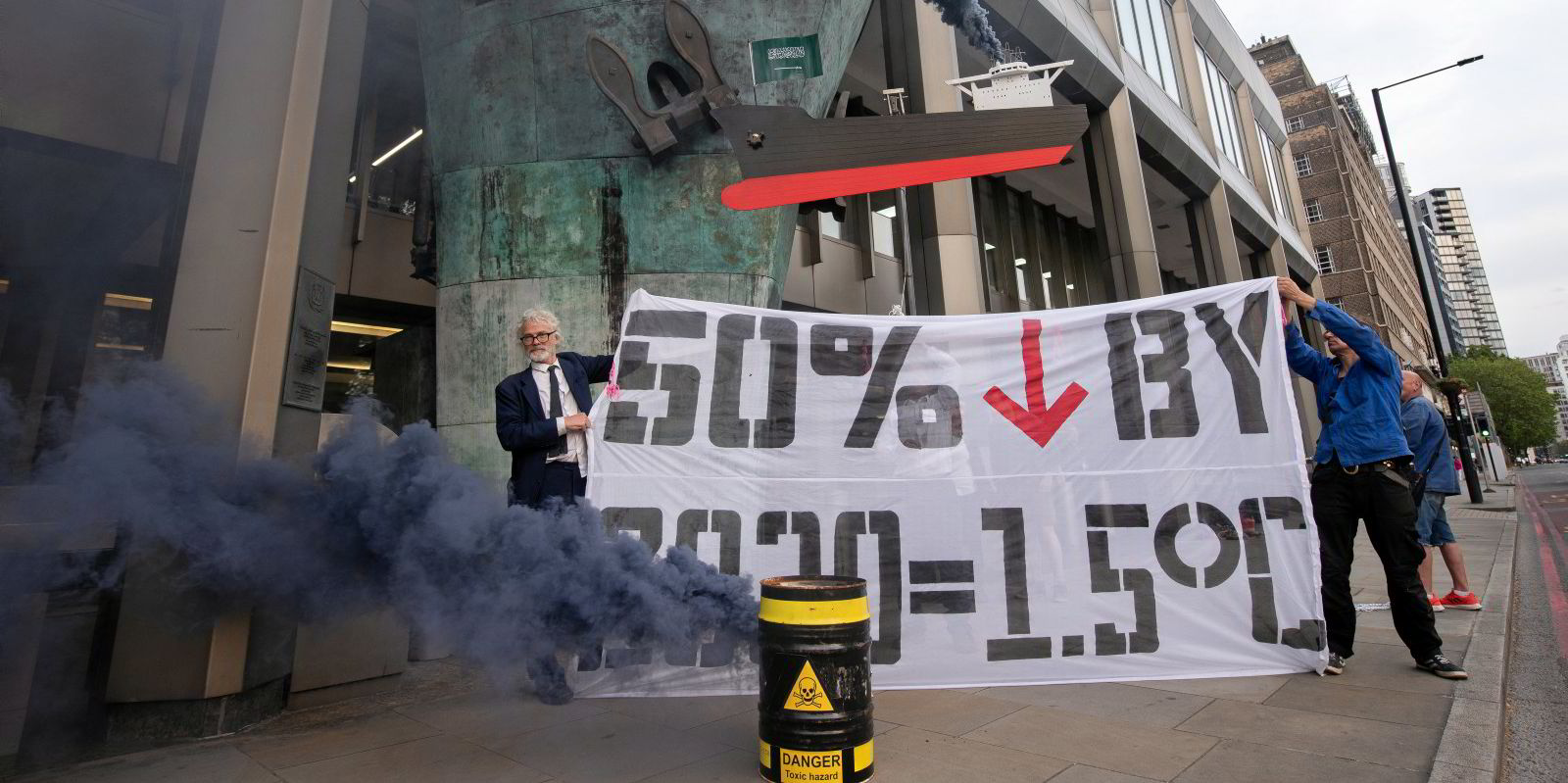

Environmental protestors were in party mood as they greeted delegates arriving at the International Maritime Organization on Monday for decisive week-long talks to raise the regulator’s decarbonisation targets.

But there was a more sombre mood in the building as the United Nations made it clear that it was unhappy with the pace of the IMO’s action on climate change and demanded more.

In a video message to delegates, UN secretary general Antonio Guterres warned: “Humanity is in dangerous waters on climate change.”

He said he wanted to see the IMO respond this week by agreeing net zero shipping emissions by 2050 at the latest.

The IMO “must move much faster,” Guterres demanded.

A representative from UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) piled on the pressure when he said: “This body has to do more now.

“If the parties represented here chose a low-ambition pathway, our ability to meet the Paris Agreement on climate change’s target will be compromised.”

As TradeWinds reported previously, a working group meeting last week at the IMO was spilt on whether it should — in a draft agreement — target net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest, or if it should set a more general target of “by the mid-century”.

There is also still an issue over intermediary targets in 2030 and 2040.

The IMO looks at least set to agree on a global fuel standard, which will phase in increasing limits for the carbon intensity of fuel.

But the IMO remains deeply divided over the market-based measures to incentivise the switch to zero-emission ships.

Norway’s Sveinung Oftedal, who chaired the working group meeting, insisted “there is a clear desire by all to resolve the remaining elements” despite the differences.

IMO secretary general Kitack Lim attempted to rally the IMO to a consensus. He said the “time for the IMO to demonstrate its global leadership is now”.

He said an ambitious agreement on climate change would be remembered by future generations.

“It will be your legacy,” he urged the IMO delegates.

Act now

Marshall Islands ambassador Albon Ishoda said the reputation of the IMO is also at stake.

“For the IMO to remain a legitimate organisation, it must act now,” he said.

Ishoda wants to see the shipping industry adopt a levy on carbon emissions to fund decarbonisation and a global fuel standard, something which is strongly opposed by the likes of China, Argentina and Brazil.

He said science shows zero shipping emissions is achievable by 2050.

“It is not the industry that is slowing us down, it is the IMO member states,” Ishoda said.

China has written to developing countries at the IMO urging them not to adopt a levy or the IMO’s proposed emissions reduction targets.

In a letter reported by the Financial Times, China said: “Developed countries are pushing the IMO to reach unrealistic visions and levels of ambition. [They are advocating] a flat [levy that] will lead to a significant increase in maritime transport costs.”

International Chamber of Shipping deputy secretary general Simon Bennett told TradeWinds that a levy is essential to achieve decarbonisation of the shipping industry.

“It looks like IMO is about to adopt some very ambitious GHG [greenhouse gas]-reduction targets for international shipping, which the industry will do everything possible to achieve,” Bennett said.

The ICS has proposed a levy system to the IMO and there are four other alternative levy proposals on the table.

“It’s not yet certain that governments also have the appetite to rapidly develop the radical measures, such as the levy-based Fund and Reward system proposed by shipowners, that will be necessary to make such high levels of ambition plausible,” he said. “We don’t want [the] IMO to set itself up for failure — what’s at stake is too important.”