Change is a constant in shipping. Big decisions can be difficult and risky to take, but identifying an overwhelming logic and then acting boldly pays dividends. It is a theme that runs through this issue of TW+.

The decision by Japan’s big three shipping groups to merge their container divisions into one liner unit exemplifies all the above, as explained by MOL president Junichiro Ikeda.

He describes the liner business’ core position within the MOL group as having become an “Achilles heel”. Eventually the rationale of linking up with the container units of NYK Line and K Line became imperative due to the changing face of the industry and world trade.

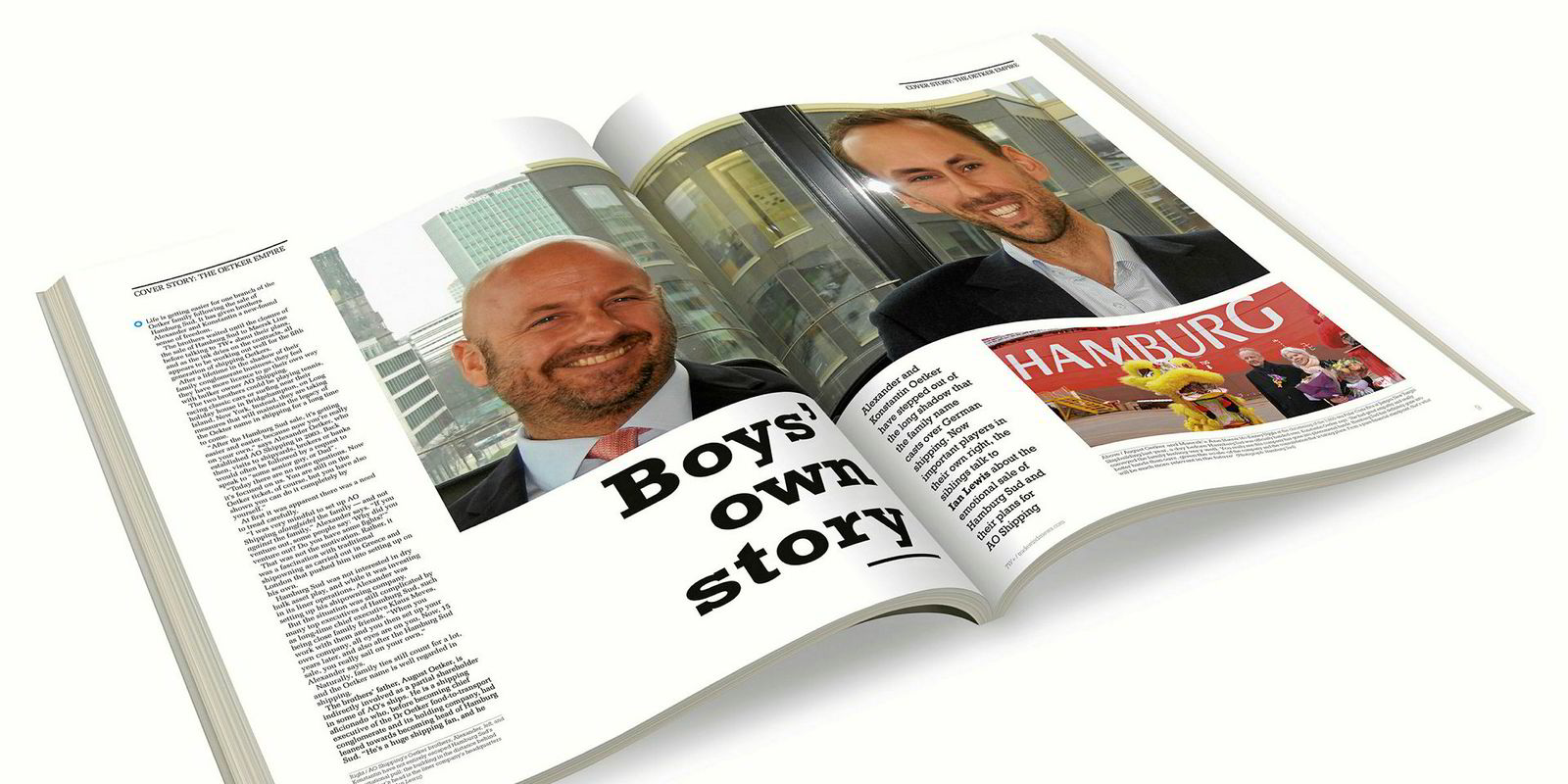

The same theme applies to the Oetker family group’s sale of Hamburg Sud to AP Moller-Maersk. Two of the sons of the Oetker dynasty express their “bitter-sweet” feelings about handing over the German liner company to bigger owners, but are also adamant it made absolute sense with the huge level of consolidation going on in container shipping.

The sale leaves them free to pursue personal interests in the equally risky asset play of owning and trading dry bulkers.

Florida’s Farrell family, owners of the Resolve salvage group, have gone the other way, deciding to invest heavily in salvage vessels and assets at a time when their main rivals were selling out to financially muscle-bound industrial groups.

Resolve now has the strength to compete internationally, while avoiding the distractions of having to pay dividends when business is just not there. But it was a big decision.

It is all about putting money where their mouths are for the Farrells, Oetkers and the Japanese groups, and the theme is reflected in the wider US shipping investment sphere, where mergers and takeovers are emerging as private equity investors decide whether to stick or twist.

The sale of crude tanker vehicle Gener8 Maritime to Euronav, at the same time as dry bulk investor Chateauban is pushing up its holding in the European owner, says a lot about the state of play in financing wet and dry bulk shipping.

It illuminates continuing power plays behind the scene, with some looking to pull out to make the best of an investment that may not have gone as well as hoped, while others eye up the potential of taking a gamble themselves.

Even a 200-year history of helping seafarers, celebrated this year by the Sailors’ Society, does not allow anyone to stand still. The basic human needs of caring and support do not change, but the way port chaplains deliver that help is always changing.

Singapore chaplain David See says seafarers used to ask for help sending postcards to their families, before the technology of keeping in touch moved on to phone cards and emails, and now most have access to social media of one sort or another.

Despite these improvements, seafarers still face loneliness and isolation — factors that are at the heart of a new film that traces the true story of a sailor who cracked under the stress of the hardships he faced on a solo circumnavigation — and then the extra strain of having to fake his progress rather than admit failure.

The Mercy, starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz, tells a human tale of pressures that many seafarers will recognise.

In some cases change appears to be coming but slowly. The issue of bribery still plagues shipping, although attempts are being made to support those on the front line who have to push back against corruption.

One retired master complains that everyone, from the top down, knows about the problems, but too few powerful organisations and institutions really support crews in trying to combat these pressures.

Crews can also bear the brunt of whistle-blowing in the US when they are detained as witnesses waiting many months for pollution cases to be heard. We examine whether this practice is counter to US law and if it benefits shipowners either.

Change is constant. It will keep on coming. Awareness and the ability to adapt and grow, even if times are hard, are paramount.