Canadian entrepreneur Mo AlGermozi has found a way to put graphene into a hull coating and apply it to ships.

The result, he said, is a coating that is tough enough to handle icy waters, does not have any biocides but keeps hull growth to a minimum and is extremely smooth so vessel performance does not deteriorate.

His start-up is Graphite Innovation & Technologies (GIT), a spin-off from his research into graphite at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia about a decade ago.

After he discovered how to make his own graphene from graphite while studying material engineering, he and co-founder Marciel Gaier launched GIT to focus on the maritime industry.

The company now has several vessels’ hulls coated with his product and has moved to bigger offices, still in Nova Scotia.

So, why does AlGermozi think he is onto something by mixing graphene into hull coatings?

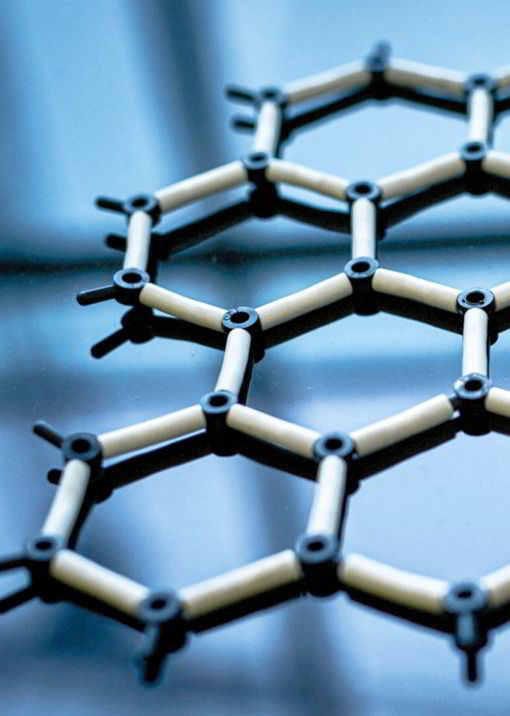

Graphene and graphite are similar, they are both pure carbon. But they are different in many ways.

Graphite occurs naturally and is commonly used but is brittle due to its plane-like layered structure.

Graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms, shaped in a tight honeycomb lattice making it extremely tough for its thickness. It also conducts heat and electricity very well.

The discovery of how to make graphene in 2004 — look up the “graphene tape test” online — not only led to a Nobel prize for physics scientists Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov in 2010, but the heralding of a new wonder material that was strong, tolerated extreme temperature ranges and was extremely light.

It was linked to uses from space travel to microcomputing. The race was on to produce it cheaply and in volume.

Scientists worldwide went to work on finding better ways to mass-produce graphene. Two of them were AlGermozi and Gaier, two researchers who teamed up at Dalhousie University in 2016.

“I was originally working on heating graphite to 3,000C when I noticed these flakes coming out of the oven,” he told TradeWinds.

This was graphene. “That was when my entrepreneurial instincts came into play,” he said of realising he had a potential commercial product.

With some early funding, his early trials were with Canada’s hydro-energy market, coating the inside of pipelines to speed up the flow of the water.

It was feasible, but the business case was not there, which is when they realised that there was a market for coating things that move through the water, rather than objects water passes through.

Dragon’s Den

Then came the job of growing the company, and seeking funding. “We went on a kind of Dragon’s Den in Canada and met John Risley,” said AlGermozi. And this changed everything.

Risley is a Canadian multimillionaire and proactive investor in clean tech. He made his millions by building up a fishing and seafood empire, so some of the first vessels GIT coatings worked with were in the fishing fleet.

Risley understood the issues, said AlGermozi, and these fishing vessels saw an improvement in fuel consumption. AlGermozi also recalled how Risley once noted that when one of his vessels went through ice there was no damage to the coating. That was the moment they became assured that their product warranted additional investment.

“We knew then we had two features and that’s appealing,” he added. There is a third unique benefit of the coating technology, they also noted. The graphene-based coating helped reduce underwater noise.

GIT now has two coatings and a propeller coating that reduces the chances of cavitation, the process where bubbles form on the tip of the propeller, reducing thrust but creating noise.

GIT has, according to Crunchbase, won $12m in funding and is expanding its market as it focuses exclusively on the shipping industry. Oslo-listed chemical tanker operator Stolt Nielsen invested in the company in 2023 as part of a series A funding round.

Reshaping the market

Since AlGermozi launched GIT in 2016, his interest has naturally gravitated towards the regulatory landscape, particularly initiatives aimed at establishing restrictions on coating composition.

There are criticisms of some self-polishing coatings over the risk of leaching chemicals, metals and microplastics into the environment.

There are concerns over some biocides due to the risks they pose in natural environments.

There are also concerns about hull cleaning due to the process often pulling away an outer layer of the coating as well as the fouling, leading to potential contamination in harbour waters.

And of course, there is the link between a smooth hull and vessel performance. Hull coating makers will talk about fuel savings from using their, usually top-of-the-range product, compared to the worst example.

A hull coating does not save fuel per se. However, it does prevent an increase in fuel consumption by preventing biofouling build-up or the coating roughness from increasing over time.

All coatings see performance deteriorate, as well as get damaged by scrapes with tugs, pontoons or underwater obstructions. Good coatings will do so more slowly.

AlGermozi said his company can now boast more than 200 vessels being coated, from smaller fishing vessels to one or two larger commercial vessels.

Stolt Nielsen announced it was coating 25 ships with the GIT solution as has Eastern Pacific Shipping.

Underwater noise

As for the cost of application, AlGermozi said it was a premium product price range.

But the coating does not need to be as thickly applied as most other coatings, he said. The claim is that only one coating of the graphene-based solution is applied to a primer or base-coating rather than two or three layers of coating for many other coatings.

It is applied to a vessel in the same way as other industrial coatings, with GIT having worked to make it as easy as possible.

AlGermozi believes he has a wonder product, one that will help shipping tackle the issue of invasive species due to biofouling, poor fuel performance due to poor hull coating condition, but also what he thinks will be the next big issue for regulators in the coming years, the reduction of underwater radiated noise.

It is a topic very high on Canada’s marine agenda due to the impact on the country’s whale populations.(Copyright)