California did not wait for the International Maritime Organization to tackle shipping’s sulphur and nitrogen emissions or the invasive species carried in vessels’ ballast water.

And officials in the state capital, Sacramento, may not wait for the IMO to ramp up its greenhouse gas emissions regulations.

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) is seeking further reductions in emissions including CO2 and other climate pollutants such as NOX, particulate matter and reactive organic gases.

According to spokeswoman Lynda Lambert, the agency is exploring regulatory and voluntary measures to reduce emissions by oceangoing vessels in transit to California ports, rather than just within them.

CARB is in the early stages of its work, but typically rulemaking takes three to five years.

When Sacramento has wielded its power over shipping in the past, some in the industry have complained about facing a patchwork of regulations, including sub-national governments such as US states, when the IMO should be there to make one set of rules for a global business.

The United Nations regulator is working to craft new measures to push shipping to its goal of net-zero greenhouse emissions by around 2050, but there are concerns about how slowly it moves.

Pacific Environment climate policy director Teresa Bui told TradeWinds in an interview in Sacramento: “The IMO, while it does have a global reach, is moving slower, and right now we’re in a decade of a climate emergency.”

The advocacy group is urging California to adopt an in-transit rule. Doing so would dovetail with the state’s requirements to cut emissions in port by using shore power.

“We need everyone to move as fast as possible,” Bui said, “and we think sub-national [governments] and ports all have a role to play in accelerating shipping decarbonisation. So we’re trying to get all entities, all stakeholders, to move as fast as possible, not just at the IMO.”

Bui said California was the first to pass a low-sulphur fuel rule that the IMO eventually adopted, which scientific data shows has had an “incredible” impact on the reduction in SOx emissions.

It also passed the first at-berth rule, which requires major ships such as cargo vessels and cruise ships to plug into shore power, “and we’re seeing the EU and China adopt similar policies”, she said.

“So as California goes, so does the rest of the nation and the rest of the countries. So we’re hoping that California can lead on an in-transit rule.”

Although California’s regulations on shipping have not directly tackled carbon at sea yet, the rules on NOx, SOx and particulate matter have what Lambert described as co-benefits for cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

But CARB sees reasons to do more.

“Oceangoing vessels are projected to be one of the largest contributors to mobile source emissions in California by 2037, and thus, there is a need for future measures to reduce emissions from this sector,” she said.

“Reducing carbon and criteria pollutant emissions from oceangoing vessels is critical to helping California improve public health, meet federal air quality standards and California’s climate-change goals.”

Pacific Environment would like California to adopt a rule that strives for zero emissions, both of greenhouse gases and other pollutants, by 2040.

Not everyone wants California to step into regulating international shipping in that way.

Here are some of the regulatory options proposed by University of California, Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy:

In-transit rule: This would require ships travelling to or from California ports to meet gradually tightening carbon-intensity limits.

Low-Carbon Fuel Standard: Shipping is currently exempt from California’s existing carbon-intensity limits. This standard could be expanded to encompass the industry.

Cap-and-trade regulation: This option could require shipping companies to buy carbon credits, similar to the European Union Emissions Trading System.

MRV: A monitoring, reporting and verification system would allow California to collect data from shipping companies and set a baseline for other regulations.

Climate Scoping Plan: This plan laying out California’s decarbonisation pathway could be revised to encompass emissions from oceangoing ships.

State port access fees: A supplemental statewide port fee could be created, with varying costs based on carbon intensity.

Vessel speed reduction: Some California waters have voluntary speed reductions, to reduce emissions and protect whales. These could become mandatory.

A global problem

Kathy Metcalf, president of the Chamber of Shipping of America, said greenhouse gas emissions differ from pollution such as SOx and NOx, which have local impacts in port communities.

“What people need to be reminded of is [that] greenhouse gases and CO2 are a global problem. It’s not a regional problem,” she told TradeWinds.

“So from our perspective, the only viable solution is a global solution.”

She said that even the EU’s carbon regulations, including the Emissions Trading System and other rules, were created to push the IMO into action. Even Brussels sees the need for a global programme.

The chamber supports a global fuel levy. Metcalf also worries that action by California could help dislocate global trade patterns and would not be able to ensure that there are green fuels in sufficient supply to meet the new regulations.

“We’ve got to get a programme that everybody can agree to … and our ultimate goal is to find a reasonable solution. We know it’s going to cost more money; it’s going to cost everybody more money,” she said.

“But we would hate to see programmes put in place that collect a lot of money but don’t result in environmental benefits.”

David Wooley, who heads the Center for Environmental Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, agreed that a global solution is ideal. But he said that works only if “you can get it done” and if it is strict enough.

He sees momentum at the IMO but also a risk of insufficient action.

“And so one of the things that will help with this is if an increasing number of national, sub-national and, in the case of the European Union, multinational movements towards regulation begin to happen,” he told TradeWinds in an interview at his office in Berkeley.

Brussels has taken action in that direction, with its emissions trading rules and the FuelEU Maritime regulation that caps fuels’ carbon intensity.

But Wooley believes Sacramento should get in the game too.

“As we were looking around at this, we realised that there’s a history of California leading in this area. And could they lead again? Our sense was that they could,” he said, pointing to the state government’s move to regulate sulphur emissions.

“That action, which was very carefully done, well-researched and supported by the staff there and the commissioners, led to action by the IMO.”

The IMO first established emissions control areas with sulphur limits, followed by a global limit on SOx emissions at the beginning of 2020.

IMO standards

California could become involved by implementing IMO standards, but Wooley said it could also provide a way to move forward if the UN shipping body stalls.

“California often leads the national government on air pollution controls, particularly for mobile sources, and this is another mobile source,” he said.

“A signal from California would accelerate this momentum and make it more likely that the IMO would adopt something that was effective and strong.”

In research led by Wooley and commissioned by Pacific Environment, the Goldman School laid out several options for California to take that leadership role.

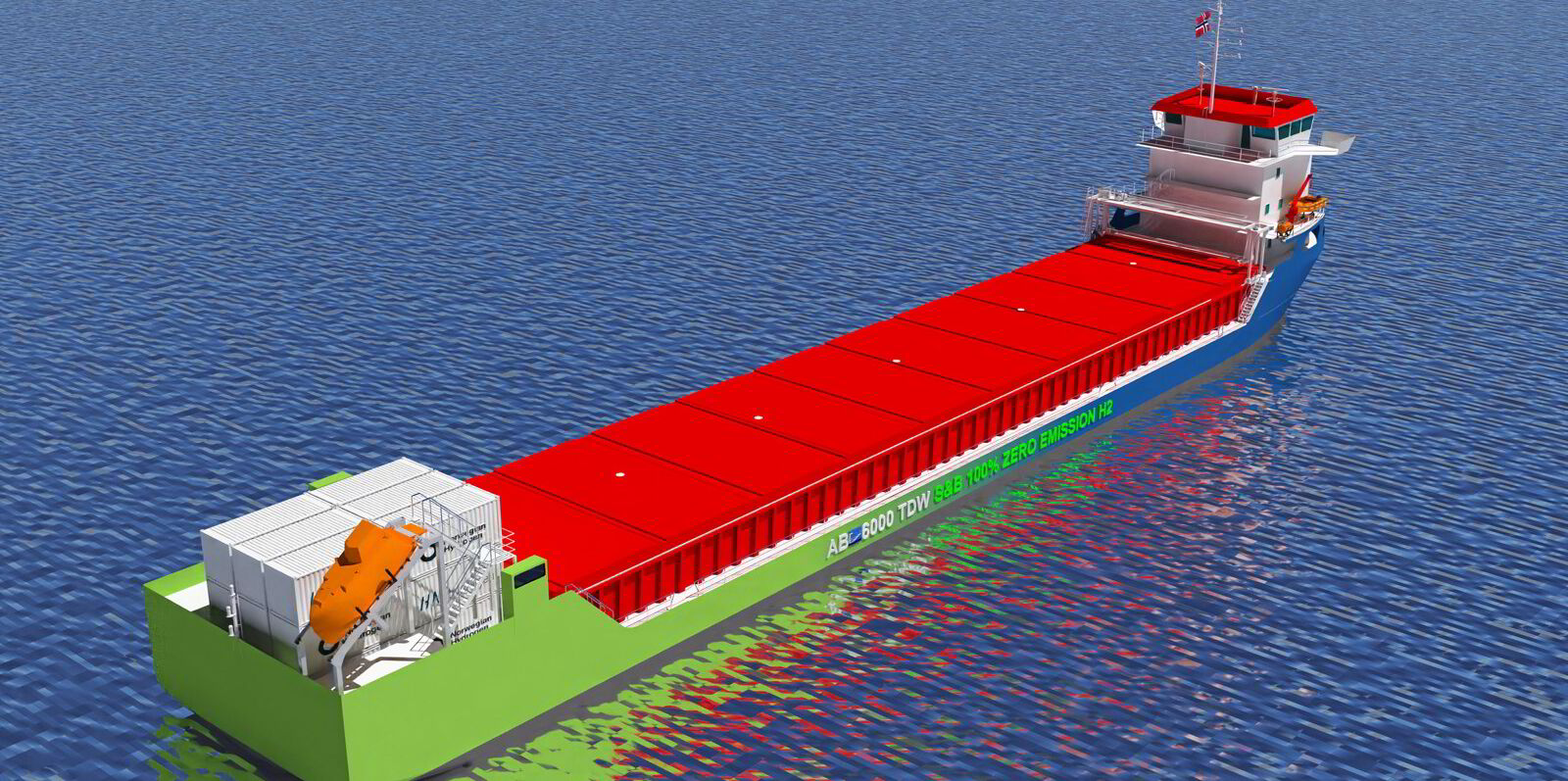

The first is to create an in-transit rule, using the template from SOx and NOx emissions to tackle greenhouse gases for voyages to and from California ports.

Ships using those ports would have to report their emissions and gradually reduce them over time.

The measure could look like the FuelEU Maritime legislation, which gradually limits the greenhouse gas intensity allowed in the energy sources used by shipping.

Wooley believes there is some appetite for this option from California officials, although he said it could take years to develop.

Another option is to create a cap-and-trade system, which could include creating a carbon credit market like the EU’s emissions trading regime.

“If the IMO did not move forward, action by California would essentially expand in a fairly big way the geographic scope of what the Europeans are doing,” Wooley said.

“And so essentially you move toward an international transition. Now it isn’t complete, because there is still a lot of shipping that never comes to California or European ports, but a lot of shipping will, and so this is an opportunity to gradually move toward a global regulatory system.”

A third option would be to expand the state’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard. Shipping is currently among the industries exempt from the carbon-intensity regulation.

In Washington DC, Congress has passed laws that pump funding into green fuels, and California has one of the hydrogen hubs created with support from President Joe Biden’s administration.

If Biden’s Republican opponent, Donald Trump, wins the presidential election in November, Wooley said it will be hard for him to stop the momentum of those investments and of the regulatory developments at the IMO.

But a Trump win could heighten the need for leadership from California, he added.

Wooley said state action would send policy signals to the industry that would provide impetus to spending on green shipping.

“I think the signal is really important here, because what I’m seeing is a really unusual situation, which is a highly polluting industry embracing change, interested in doing the transition [and that] has begun to invest fairly heavily in that,” he said.

“But at the same time, in order to keep that moving, they need, essentially, a signal that regulation is coming.”(Copyright)