The US’ presumptuous worldwide maritime pollution enforcement regime violates foreign seafarers’ basic human rights and the treaty itself.

The practice needs exposure and reform, but in the meantime, there are steps shipowners and managers can take to limit their crew’s personal exposure and their own economic costs.

Historically, in the negotiations that led to the Marpol treaty, the US unsuccessfully pressed for enforcement to be put in the hands of port states. Instead, the treaty gave enforcement to flag states, but let port states arbitrate before the International Maritime Organization against flag states in cases of deficient enforcement.

US negotiators told the US Senate that such arbitration would be an “important lever”.

It’s a lever the US has never employed.

Instead, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) bypasses the prescribed international enforcement regime, wrongfully abusing foreign crews.

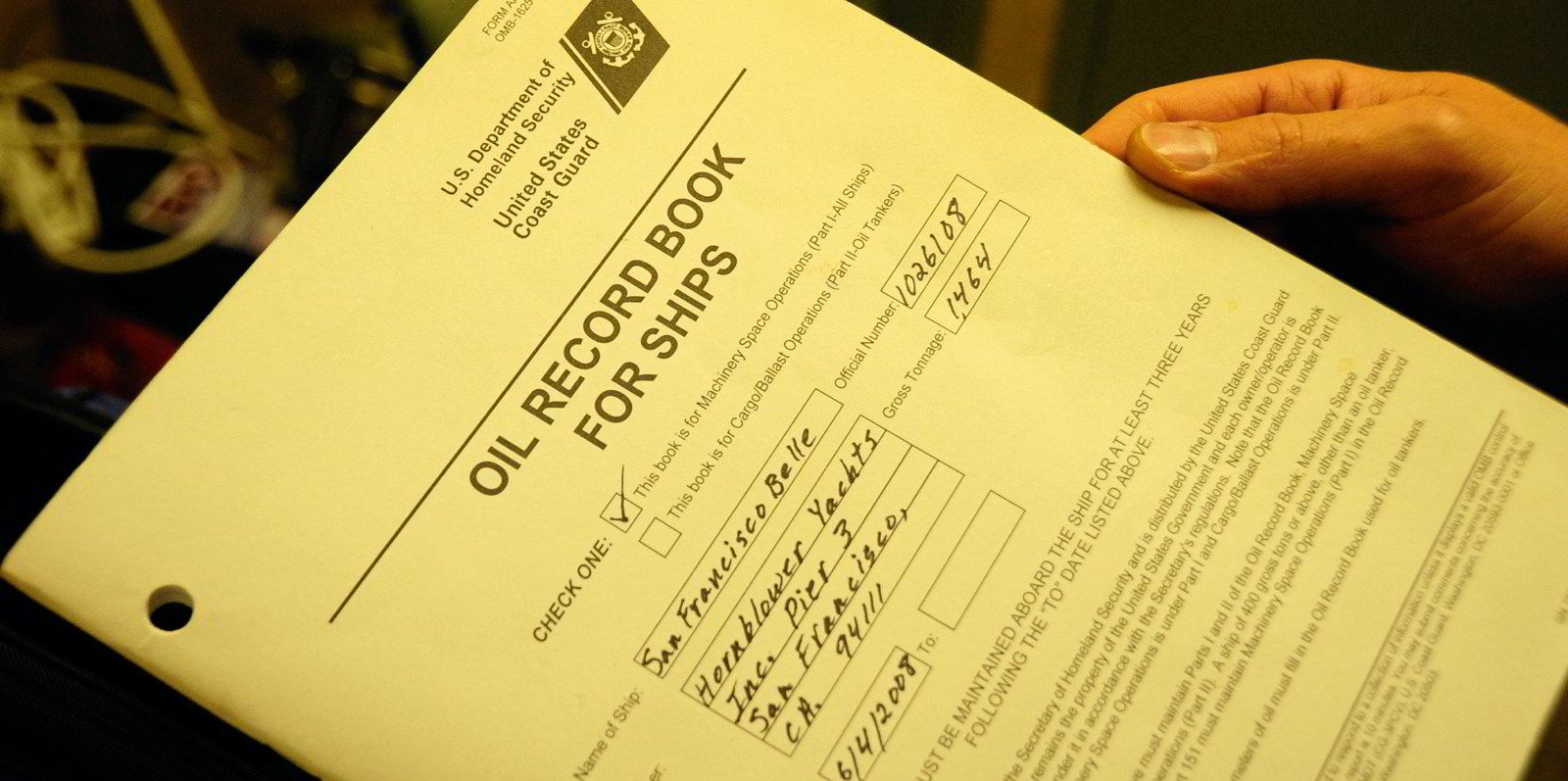

Here’s how it works: Under Marpol, flag states require vessels to keep environmental compliance records, including an oil record book (ORB). US regulations implementing Marpol require foreign vessels to make entries and keep records, but only “while in the navigable waters of the [US]”.

However, US officials interpret an odd provision in the regulations to make it a crime for a foreign vessel merely to possess an ORB with incomplete coverage of high-seas events.

Where Marpol itself specifies that vessels “shall be provided with an ORB”, parallel US regulation requires them to “maintain an ORB”.

The deviation arose when the US Coast Guard carried forward older, pre-Marpol US regulations that included the “maintain” language. The limitation to “within the navigable waters of the [US]” was gotten around when DOJ lawyers argued that “maintaining” a record while here makes pre-arrival foreign ORB entries subject to US criminal penalties. Judges have generally acquiesced in this reading.

The DOJ reaches beyond vessel owners and managers and seeks US criminal penalties, including prison, against foreign crew members, typically focusing on chief engineers, if their actions allegedly “caused” a master to “fail to maintain” a complete and accurate ORB upon arrival.

When America’s desire for port state enforcement ran into logistical difficulties, the DOJ was even more creative. Since Marpol and even US law itself contemplate flag state enforcement, port state inspections are supposed to be expeditious, and vessel owners have the right under Marpol to sue port states that cause unreasonable delay.

But by US statute, vessels can be sold to pay fines, and the DOJ can demand a “bond or other surety” to release a vessel under such circumstances. Such surety gives the DOJ leverage to hold potential witnesses — usually the engine crew and the master — as human collateral, by means of an “Agreement on Security” with the ship operator that prohibits the vessel’s departure until the demanded crew comes ashore.

Once they do come ashore, foreign crew members are often held in the US for a year or more without seeing a judge or being told of their rights. If crews object, the DOJ typically asks a judge to arrest them as “material witnesses”. Arresting witnesses is exceedingly rare in US criminal proceedings, but judges routinely allow it in Marpol cases. One judge signed a warrant to arrest a ship’s electrician even though the DOJ provided no information about him and did not mention his name in its supporting affidavit.

Asking a court for an arrest warrant, however, triggers a measure of judicial oversight that can be used in the crew’s favour. Most judges will require that detained crews be allowed to give prompt deposition testimony and depart.

Our firm and others have been able to arrange expedited depositions, protecting all interests and preserving testimony for all. The DOJ inevitably argues for prolonged detentions and protracted investigations, and opposes depositions, preferring to hold its hostages until trial. It, therefore, seeks to negotiate its “Agreement on Security” in confidence with the crew’s employers — without the consent of the crew and without judicial involvement.

The costs to the ship owner, manager, and crew are extraordinary.

Housing, feeding, and paying detained crews while the DOJ investigates and interrogates can cost $50,000 per month or more. In no other context are US criminal targets required to pay for the investigation. Crew members miss birthdays, funerals, weddings, important holidays, graduations and the opportunity to advance their careers. They are usually held in remote hotels with limited social interaction.

Although we favour enforcement of pollution control laws, the harsh US system is disproportionate and even dishonest: in videos that can be seen on YouTube, a government prosecutor promises handsome rewards to crews who report foreign Marpol violations to US officials. But the videos don’t mention the detentions.

The international community should insist on a return to flag state enforcement. In the meantime, seafarers’ rights in the US should be vigorously protected. Shipowners should refuse to force crews ashore, absent judicial supervision or the crews’ express consent. Crews should be fully compensated for missed work (even if they are allowed to return home), and they should be informed of their rights.

Edward MacColl and Marshall Tinkle are attorneys

at law firm Thompson, Maccoll & Bass

Do you have an opinion to share?

Email: news@tradewindsnews.com