The Jones Act has committed supporters and it has fierce critics.

For both, the 1920 law is known for this: reserving domestic trades to ships that are built at a domestic shipyard, crewed by Americans, controlled by a US company and flying the Stars and Stripes.

But a new book by maritime lawyer Charlie Papavizas, who researched the 144 years of American history leading up to the law’s passage, concludes that Senator Wesley Jones probably would be “chagrined” to learn what the act that bears his name is known for today.

“The ‘Jones Act’ was about foreign trade, not domestic trade,” Papavizas writes in Journey to the Jones Act, which explains that the law formally known as the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 was intended to pave the way for selling off a massive government-controlled fleet of cargo ships built to keep trade flowing and supply the US armed forces upon the outbreak of World War I.

“Jones probably would not be amused … by the many mischaracterisations that have taken hold, including that the US reserved its domestic trade to US-flag vessels in the ‘Jones Act’.”

Papavizas told TradeWinds that he embarked on the book to fill a gap in the public discourse about the act.

Although it is typically described as the law that reserved trades between two US ports for American-built ships, the lawyer traced the roots of that protection for domestic shipping back to the country’s founding, well before Jones had anything to do with it.

From America’s start

What we now call the Jones Act is the codification of US merchant marine policy leading up to the 1920 law.

“If I have to read one more time that it’s a 100-year-old law, I’m going to throw up,” he said. “It’s been embedded in our country’s laws from the beginning, and virtually at every point in which it’s been touched by Congress, no one thought it would be controversial.”

He said that was the case in 1789, when the US Constitution was signed, or in legislative developments leading up to the 1920 Jones Act, which he described as “tinkering” with the fundamental precept that domestic trade should be reserved for American citizens.

It is certainly controversial now.

Just last month, Utah governor Spencer Cox signed a resolution encouraging US Congress to repeal the Jones Act.

Maritime lawyers refer to the Jones Act in another context. The legislation is also commonly associated with US law protecting seafarers when it comes to personal injury while working.

This is also not core to the 1920 law championed by Senator Wesley Jones, according to maritime attorney Charlie Papavizas.

He said that when his children were younger, they would search for “Jones Act lawyer” on Google and find personal injury specialists.

“Dad, you’re not one of those,” Papavizas recalled them saying. “You’re not a Jones Act lawyer.”

The bill had passed both houses of the landlocked state legislature with resounding majorities. Its text argues that the Jones Act “dramatically” increases the cost of purchasing, staffing and maintaining ships.

“The high cost of constructing shipping vessels in the US diminishes the size of the US shipping fleet, increases its age, increases fuel costs due to age, increases maintenance costs due to age, and increases crewing costs due to age and a lack of automation,” the Utah bill reads.

“All other modes of domestic transportation in the US are permitted to use foreign manufactured equipment for commercial operation without restriction, including aircraft, railroad cars and locomotives, trucks, automobiles and mass transit vehicles.”

After 100 years, why does it matter that the Jones Act is known for something its namesake senator was not focused on in its passage?

Papavizas, a Washington DC-based partner at law firm Winston & Strawn who works as a lobbyist for maritime companies, said the parts of the US law that reserve domestic shipping to American citizens are no different from other countries’ laws, and are similar to the rules in trucking and aviation.

What is different is the requirement that the ships be constructed at a US yard, but he said that is aimed at sustaining the already-small domestic shipbuilding base.

Papavizas described the argument that the US could save its shipyards by making them compete against the likes of China’s yards as naive.

“That doesn’t make any sense to me, and by the way, it didn’t make any sense to people in 1880 and 1890 and 1910,” he said. “The same things were said then.”

Keeping up with Senator Jones

In his day, the strait-laced Senator Jones was perhaps not best known for his support of the US-flag merchant fleet but rather for his dedication to ending what he saw as the scourge of alcohol.

The lawmaker from the state of Washington was a national leader of the prohibition movement during his long career in Congress, first in the House of Representatives and then in the Senate.

Papavizas writes that Jones argued for enforcement of the ban on alcohol when it became the law of the land in a 1919 amendment to the Constitution.

“[The] law must be enforced or orderly government will fall,” the senator said.

But after World War I ended, Jones’ role as the Senate Commerce Committee chairman put him at the centre of an effort to solve a problem.

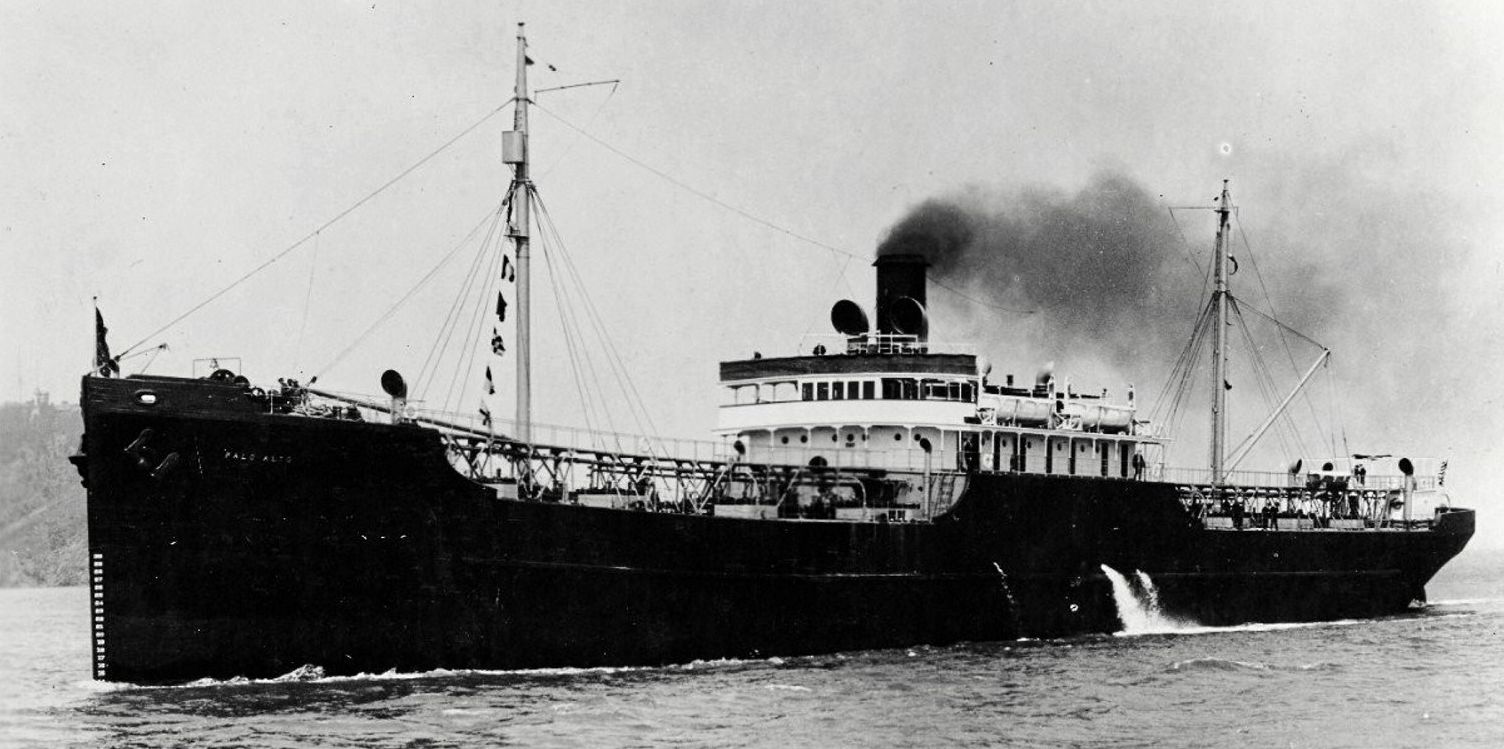

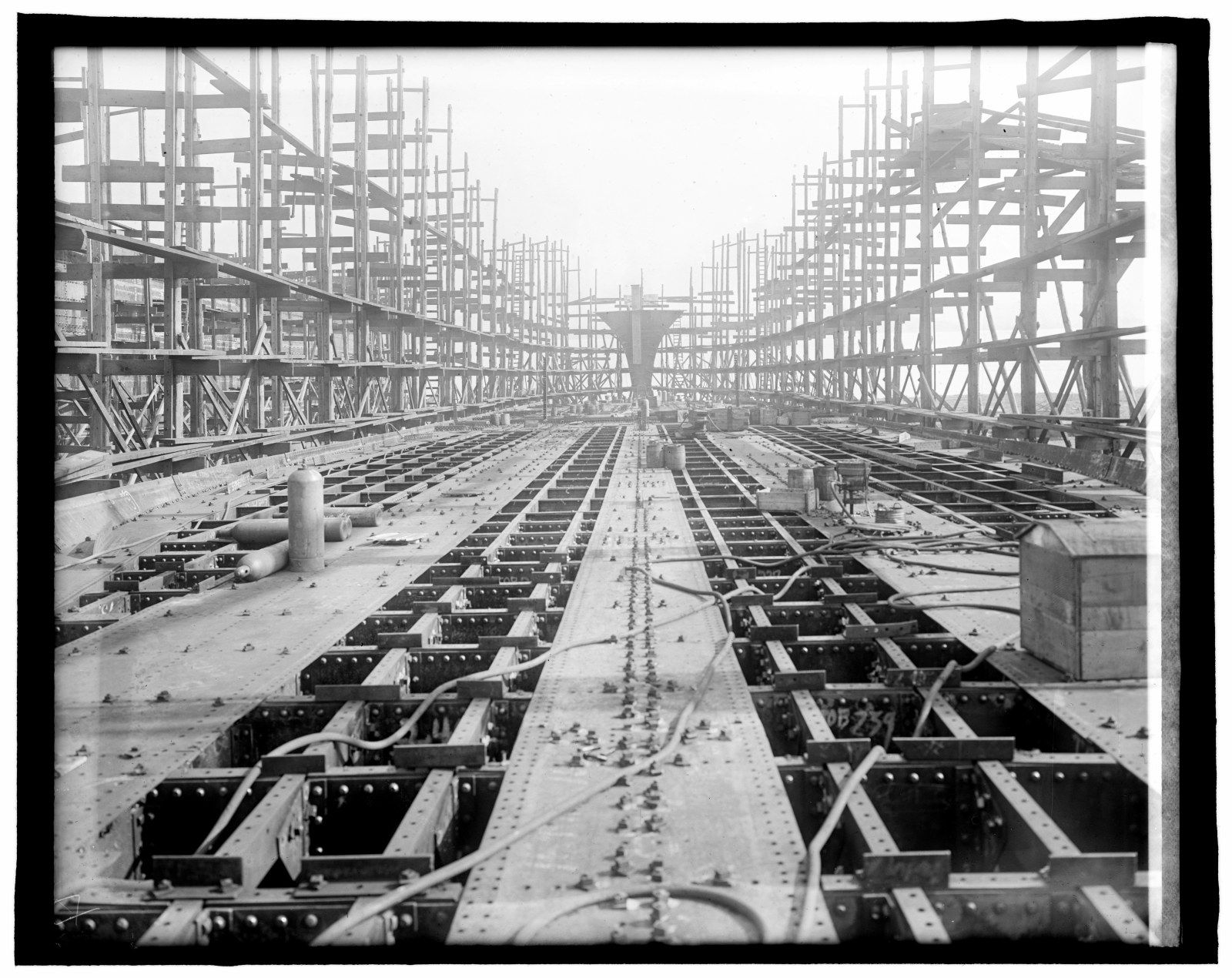

The federal government confronted its need for a fleet of merchant ships under US control through a vast shipbuilding programme, comprising nearly 3,300 newbuildings with a combined capacity of 18m dwt.

It was estimated to be the largest shipping fleet owned by a single organisation or government. Some vessels were commercially useful, some were not. Some were made of concrete (yes, that was a thing).

The Merchant Marine Act, later dubbed the Jones Act, was the game plan for what to do with these ships.

“Senator Jones made it obvious from the beginning that he was serious about developing a comprehensive plan,” Papavizas said of Jones, who was known as one of the Senate’s hardest-working members.

He introduced two overlapping bills intending to get the government out of the shipping business, without giving away the taxpayers’ enormous assets.

But the privatisation of the giant Fleet Corp shipping business included a declaration that an American merchant marine was necessary for national defence and the growth of international commerce.

“We do not desire, and it is not our purpose, to drive other nations off the sea, but we do want to do, and ought to do, at least our proportional part of our own and the world’s carrying trade, so that our commerce shall have a fair chance in the world’s markets, and that we may be hereafter fully prepared for any emergency that might confront us,” Jones said in Congress.

Although the focus was the role of US-flagged vessels in international trade, both bills had an impact on domestic “coastwise” commerce.

Some of this came in the form of clawing back exemptions to previous protections, such as repealing a 1917 permission for foreign-built ships in the coastwise trade, according to Journey to the Jones Act.

But they also proposed protections on coastwise trade to US territories, Papavizas writes. At the time, that included the Philippines.

Jones presided over commerce committee hearings that the lawyer describes as “intense” and that resulted in proposed legislation stating that the US needed a merchant marine “to carry the greater portion of its commerce” and to act as a naval auxiliary, for national defence and both foreign and domestic trade.

The bill for the first time included a US-build requirement as a qualification for domestic trade, yet Papavizas writes that this was already mandatory for American vessel registration, and its inclusion in the Jones Act was to put a lid on further relaxation of those rules.

Also important to Jones was the imposition of duties that favoured US-flagged ships and discriminated against other nations’ vessels — so important that the bill “authorised and directed” the president to tear up treaties that restricted the government’s ability to impose them, Papavizas writes.

The bill made it to President Woodrow Wilson’s desk in June 1920.

Before signing the bill into law, Wilson told his cabinet that he favoured freedom of the seas, but he wanted the American flag to be a part of it and was “strong for” the US merchant marine.

It was a time, as it was for America before the Jones Act, when US-flag shipping held importance up to the Oval Office.

“During that period, 1776 to 1920, it genuinely was a national story … It was a story that the president cared about and Congress cared about, and the pundits cared about and newspapers cared about,” Papavizas said, acknowledging that the topic is more peripheral today.

Of course, Jones’ passion for eliminating alcohol from American life was less successful, with a 1933 constitutional amendment ending prohibition, but he was committed.

“He rode that horse too long,” Papavizas told TradeWinds. “When the country had decided that was a bad idea, he kept going.”

Papavizas wrote his book in the hope that it will show how rich merchant marine policy is in the US and provide insight into how intertwined it is with the nation’s history.

He concludes in his book that the Jones Act did cement into law the necessity of having a US-flag merchant fleet trading in international markets.

But why did the law become known for other things? Journey to the Jones Act stops at its passage in 1920.

“What occurred after is a tale for another book,” Papavizas writes.