Here is a phrase you may not have used since your university political science class: civil society.

As shipping tackles its environmental footprint, particularly its greenhouse gas emissions, civil society is seen as a key factor in pushing the industry towards a greener future.

It is the term for the ecosystem of non-governmental organisations that work to shape policy, that research the avenues for change and the consequences of actions or inaction, and that represent the voices of a multitude of interests.

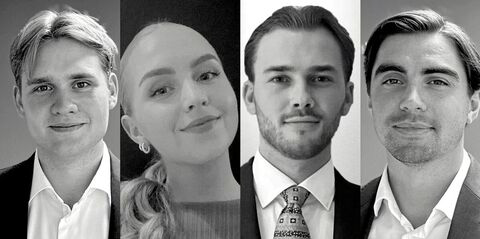

Most of the figures featured in the TW+ Green Power list of advocates are part of civil society, although the list includes the lawmakers and regulators who are also influencing the pace of shipping’s transition towards greater sustainability.

And although the names in the pages that follow represent a small slice of civil society — which includes environmental groups, industry associations and decarbonisation centres — some experts believe there is room for more voices in the policy debate.

A report released during the October annual summit of the Global Maritime Forum found that civil society involvement in the path to bring zero-emission fuels to the shipping business is “partially on track” because of the need for even more representation in the discussions.

The report — by consultancy UMAS and the United Nations Climate Change High-Level Champions, with the Global Maritime Forum’s Getting to Zero Coalition — checked the progress towards a key goal of the International Maritime Organization: to have 5% of shipping’s energy coming from scalable, zero-emission fuels by 2030. Its authors described civil society input as a key lever for shipping’s decarbonisation.

The report carried out by UMAS the UN Climate Change High-Level Champions for the Getting to Zero Coalition found civil society on track only in two out of five areas that are key to the IMO’s zero-emission fuels goals.

| Indigenous groups, small-island developing states and least-developed countries become more prominent, with increased participation in shipping decarbonisation negotiations | Partially on track |

| Observers in the IMO increase focus on climate | Partially on track |

| Key labour organisations voice support for decarbonisation | On track |

| Green skills gaps identified and recommendations in place to address those gaps for both jobs at sea and across the supply chain | Partially on track |

| Local NGOs supporting top-50 global ports calling for air pollution mitigation | On track |

There are already 88 non-governmental groups with consultative status at the IMO, and the report’s authors wrote that multiple NGOs have been involved in the debate at the UN regulator in the past year.

The authors of the study say that representatives of a diverse range of communities must play a role in decarbonising shipping. That includes voices from small island states, least developed countries, indigenous groups and port communities.

“As the adoption of scalable zero-emissions fuels gathers pace, civil society plays a crucial role, not only in facilitating decarbonisation on the grounds of its societal and environmental importance, but in ensuring that the economic benefits of new scalable zero-emissions fuels production, green corridor initiatives, and supply and bunkering developments are accessible to all, including the remotest communities,” the report’s authors write.

Progress has been made in key areas.

The report highlights the role of the International Transport Workers’ Federation in committing seafarers to decarbonisation while also mapping out a pathway to a just energy transition.

At the IMO, the Inuit Circumpolar Council, an indigenous group spanning four Arctic countries, earned consultative status in 2021. Also gaining the ability to participate in IMO debates were the Zero Emission Ship Technology Association and the Environmental Defense Fund.

Domagoj Baresic, a research fellow at University College London’s UCL Energy Institute and the lead author of the report, tells TW+ that environmental groups have had an impact at two key levels.

On the national and local stage, they have been instrumental in highlighting the impacts of climate change and air pollution, as well as informing governments of the best available science.

In IMO negotiations on decarbonisation, such organisations were key in providing information and bringing the debate forward.

Another important contributor is academic institutions such as UCL and decarbonisation centres, which provide research and insight into avenues for action.

But that is not enough. The report found civil society progress on track in only two of five areas.

“Progress needs to continue, and the further involvement of a range of actors across different communities, regions and backgrounds is more necessary than ever to ensure the adoption of scalable zero-emission fuels is done in a way which is equitable,” the study’s authors write.

Baresic says transitions like the one shipping has embarked on to decarbonise require buy-in from multiple stakeholders. The researchers feel that one area that is not studied enough is the role of civil society in that transition, including the roles of NGOs and underrepresented groups.

“You need these stakeholders in order for this transition to take place, because without them supporting the transition, it will not take place,” he adds.

“The other perspective is, even if you could argue that it could take place without some of these stakeholders, that it would not truly be a transition that you would want to have. In order for this transition to be truly representative of everyone, you need to have it inclusive of these various voices.”

One area in which there is a particular need for additional voices in decarbonisation discussions is the developing world, or what is known as the Global South.

At the IMO, delegations from developing countries have expressed an array of concerns; it has been far from monolithic.

Where some nations have been worried about the negative consequences to their economy of policy mechanisms to decarbonise shipping, others that are particularly vulnerable to climate change have urged more ambitious actions. Some nations are worried about being frozen out of technology developments, while others see the opportunities of green fuels production but need investment to capitalise on it.

However, John Maggs, president of the Clean Shipping Coalition, says those voices are almost exclusively from governments, not from civil society in those countries.

Those governments’ concerns about the economic impact of decarbonisation make sense, he says. After all, the least-developed countries also have high levels of poverty.

But Maggs, who is also shipping director for environmental group Seas at Risk, points to research by consultancy CE Delft showing that shipping could reach a 47% cut in emissions by 2030 with just a 10% increase in operational costs.

He says it would be better to have a more detailed understanding and analysis of the implications of policy changes: “I think that would be different if we had other voices from those different parts of the world.”

But at the IMO, does the proliferation of environmental groups with observer or consulting status bring extra complexity to negotiations that already involve an array of interests from around the world? Maggs does not think so, because they are “massively outnumbered” by groups from various segments of the maritime industry.

The IMO’s list of groups with consultative status ranges from the International Chamber of Shipping — an association of national shipowners’ groups that has played an active role in policy — to organisations representing specific maritime segments, including providers of the technologies that could make the industry greener.

Broad-based civil society participation is a good thing, Maggs says. “It means not just that you’re getting more perspectives, but you’re also covering more of the issues.”

While much focus is on climate change, he says so many other environmental impacts of shipping need to be addressed.

As the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, a treaty known as Marpol, reached its 50th anniversary this year, Seas at Risk published a report exploring the multitude of consequences of the growth in maritime trade.

Greenhouse gas emissions are an important one. While shipping accounts for 3% of emissions today, that could rise to an estimated 17% if it does not carry out reductions in line with its fair share, according to Seas at Risk.

Greenhouse gases are just one form of air pollution from the industry. After the IMO capped sulphur emissions at the beginning of 2020, the report says low-sulphur fuels are still believed to be responsible for about 250,000 deaths and 6.4m childhood asthma cases annually.

Seas at Risk also points to intentional oil discharges and risks of accidental spills, lost containers at sea and toxins in anti-fouling paints.

For Baresic, shipping’s march to greener fuels would also benefit from expansion of the geography of decarbonisation research centres. With the Maersk Mc-Kinney Moller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping based in Copenhagen and the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation headquartered in Singapore, not to mention UCL’s location in London, there are benefits to a regional perspective.

“Geography does play a role. It plays a role in who you interact with on a day-to-day basis, on whose perspectives you listen to … There’s this balance between a global industry and local concerns,” Baresic says. “We want to have those types of debates taking place in other countries as well” — and those should include the Global South.

Read more

- Green Seas: As right whales face extinction, ships are flouting speed rules that protect them

- Eneti scores contract for wind vessel newbuilding as ‘market fundamentals remain strong’

- Podcast: The future of ship recycling after the Hong Kong Convention

- Ports seen as ‘key node’ in UK’s cross-sector efforts to decarbonise freight transport

- US offshore wind vessel orders accelerate at a crawl as shipyards struggle