Technology on ships is undeniably becoming increasingly automated, with the industry moving ahead faster than regulators. That widening gap is likely to create increasing problems.

Last week’s International Maritime Organization meetings of the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) heard from the working group trying to set the basic prerequisites for creating a Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship (MASS) code.

Progress has been slow, it appears, and the prospects of a goals-based code being produced as hoped for in 2025 are sounding increasingly remote.

A big part of the problem remains the lack of a common understanding of what is meant by terms such as automated equipment or autonomous vessels. New rules will then need to be applied across regulatory conventions covering different aspects of safety at sea.

Beyond that basic requirement, it is difficult for regulators to understand what the implications will be of technological systems not yet in wide use beyond pilot projects, or that are only in early development — sometimes just in the minds of digital engineers.

As it stands, remotely controlled domestic voyages can be allowed by individual nation-states, but there are no common rules to allow services between different countries.

Legal aspects as to who is responsible if an accident occurs — the shipowner, technology developer, master of the ship or remote operator — are among the most problematic.

Systems must reduce risk, improve safety and enhance profitability if they are to be adopted for commercial use.

A proposal was tabled by Germany, the Netherlands and the International Chamber of Shipping to the latest MSC meeting seeking to allow trials of automated systems to go ahead, but there was no time to consider it.

It seeks permission from maritime administrations for an officer of the navigational watch to act as the sole look-out in periods of darkness, in accordance with the interim guidelines for MASS trials under the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification & Watchkeeping for Seafarers.

If agreed, it could be a step towards introducing enhanced navigational automation, without trying to bring along the “everything, everywhere, all at once” of fully autonomous shipping or its regulation.

It is a stepwise approach that some bigger technology groups already look to be moving beyond as they take over companies developing various technologies to try to build integrated systems that essentially make a ship a single operational digital system.

It is a neat ambition, and may well be the end result, but it is a hugely daunting undertaking.

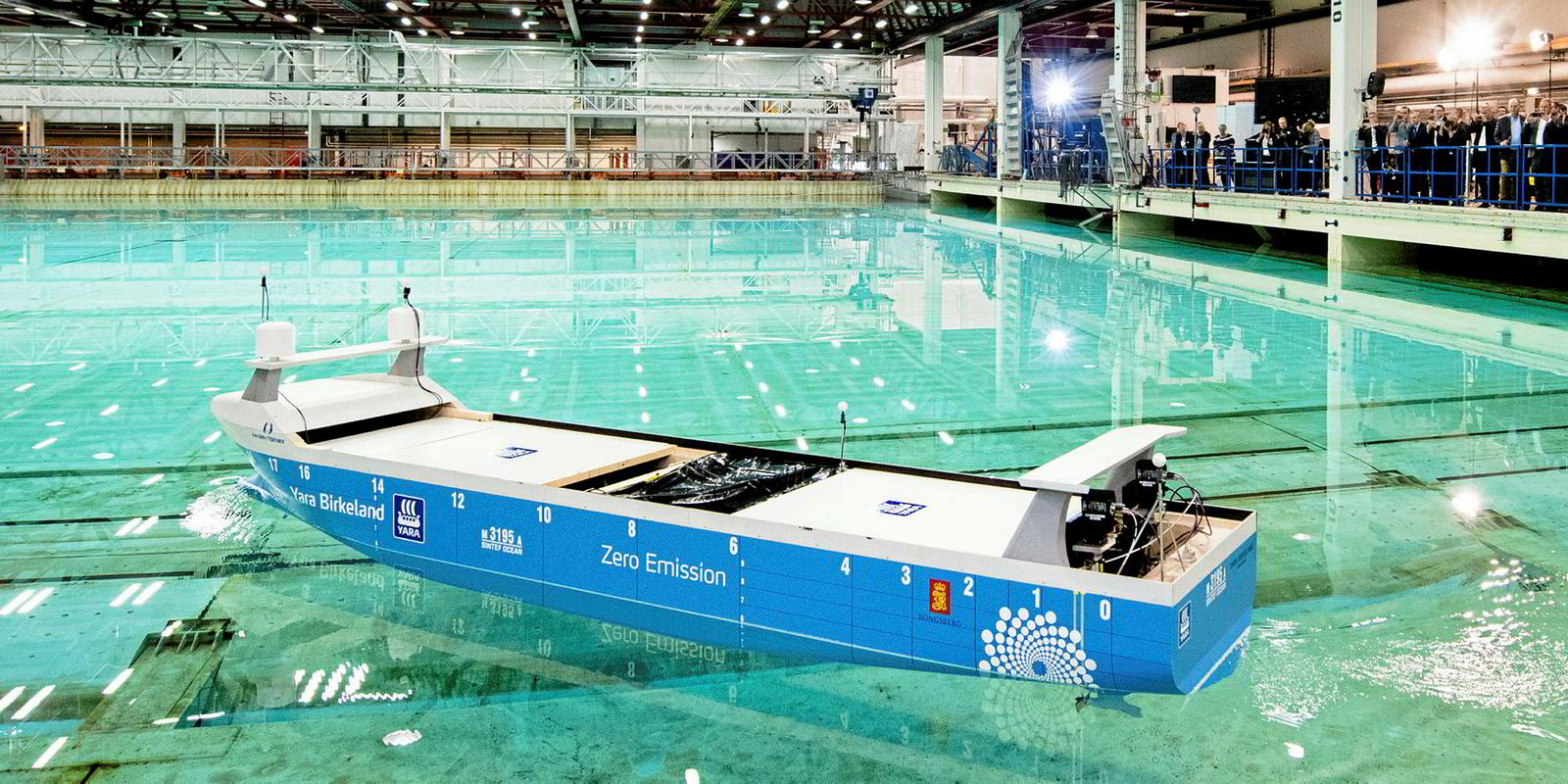

Last week at Nor-Shipping, Kongsberg Maritime took steps in that direction when it launched its K-Chief marine automation system, offering shipowners a single operating platform that integrates all Kongsberg equipment on board.

But a fundamentally different approach is being tried by Israeli collision-avoidance system developer Orca AI.

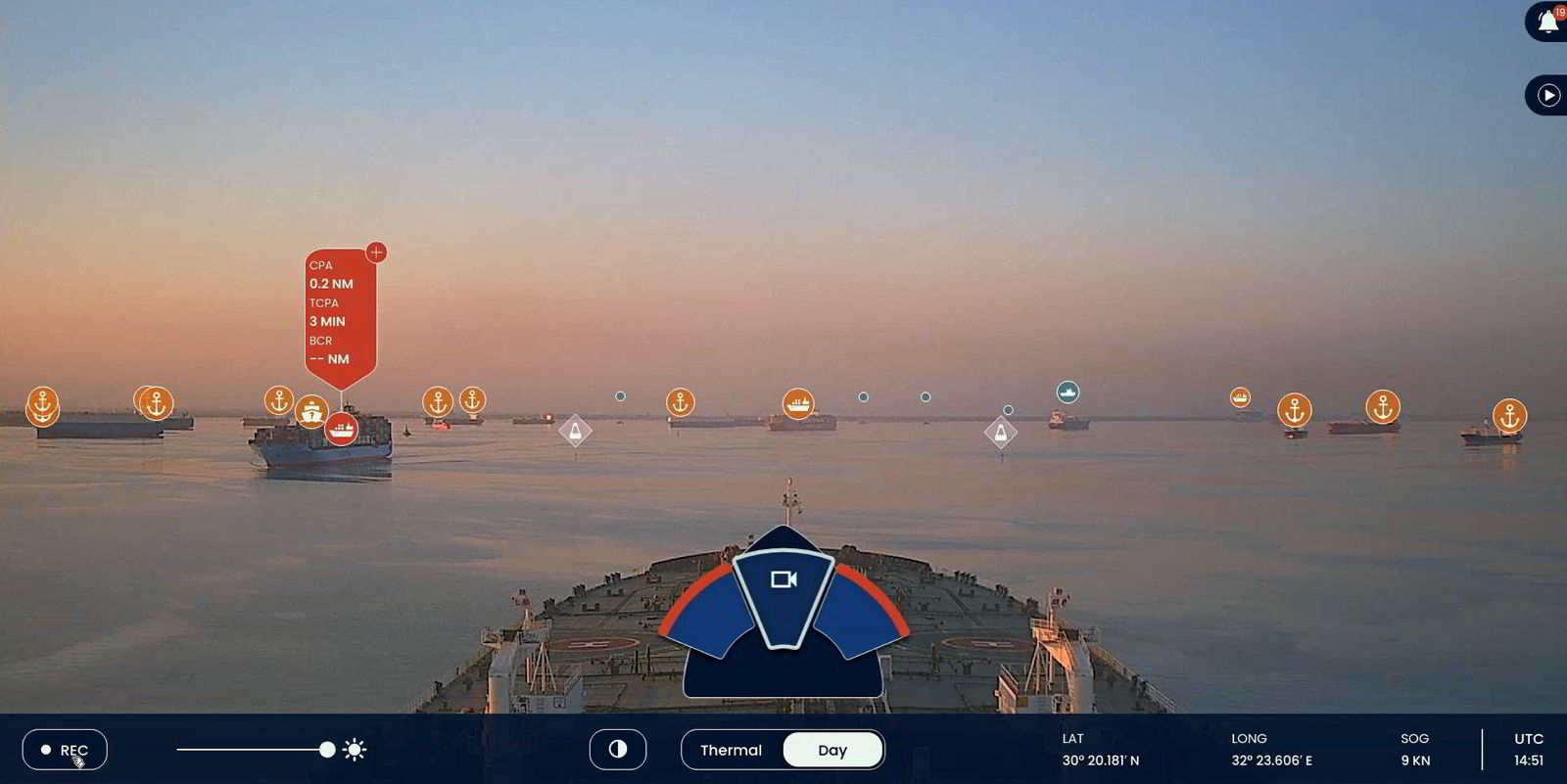

Despite demonstrating a 790-km (480-mile) autonomous remotely controlled cargo ship journey through Tokyo Bay in cooperation with NYK Group in February 2022, the company is focused solely on developing better automated navigational systems rather than on an overarching set-up.

Both companies spoke at an event held during the MSC session.

Kongsberg vice president of remote operation solutions Anton Westerlund said the company is preparing for a concept of a “system of systems” with which it can help support operators through service agreements on vessels’ equipment.

In contrast, Orca co-founder and chief technology officer Dor Raviv told TradeWinds the company wants to grow, and its kit is now on board 600 ships, but it will not expand into other digital areas because it has enough work on its hands building collision-avoidance systems.

Raviv and NYK’s manager of its autonomous ship team, Jun Nakamura, stressed that the Tokyo Bay project took an extremely challenging two years to develop the hardware, software and algorithms for an automated navigational system that could be integrated with other equipment on the 1,800-dwt Suzaku (built 2019).

The two companies continue to work together to advance computer vision and develop commercial navigational aids that can improve on what humans can see and respond to when watchkeeping and thereby increase safety and cut costs by allowing a single person to control a ship from the bridge.

Automation is on its way, but the distance to full autonomy is possibly stretching out. Approaches such as the German-Dutch-ICS proposal to allow more trials of automated systems look to be a sensible way forward.